The Extraordinary Gift of Deep Adventure

By: LOWA Pro Team Athlete Sunny Stroeer

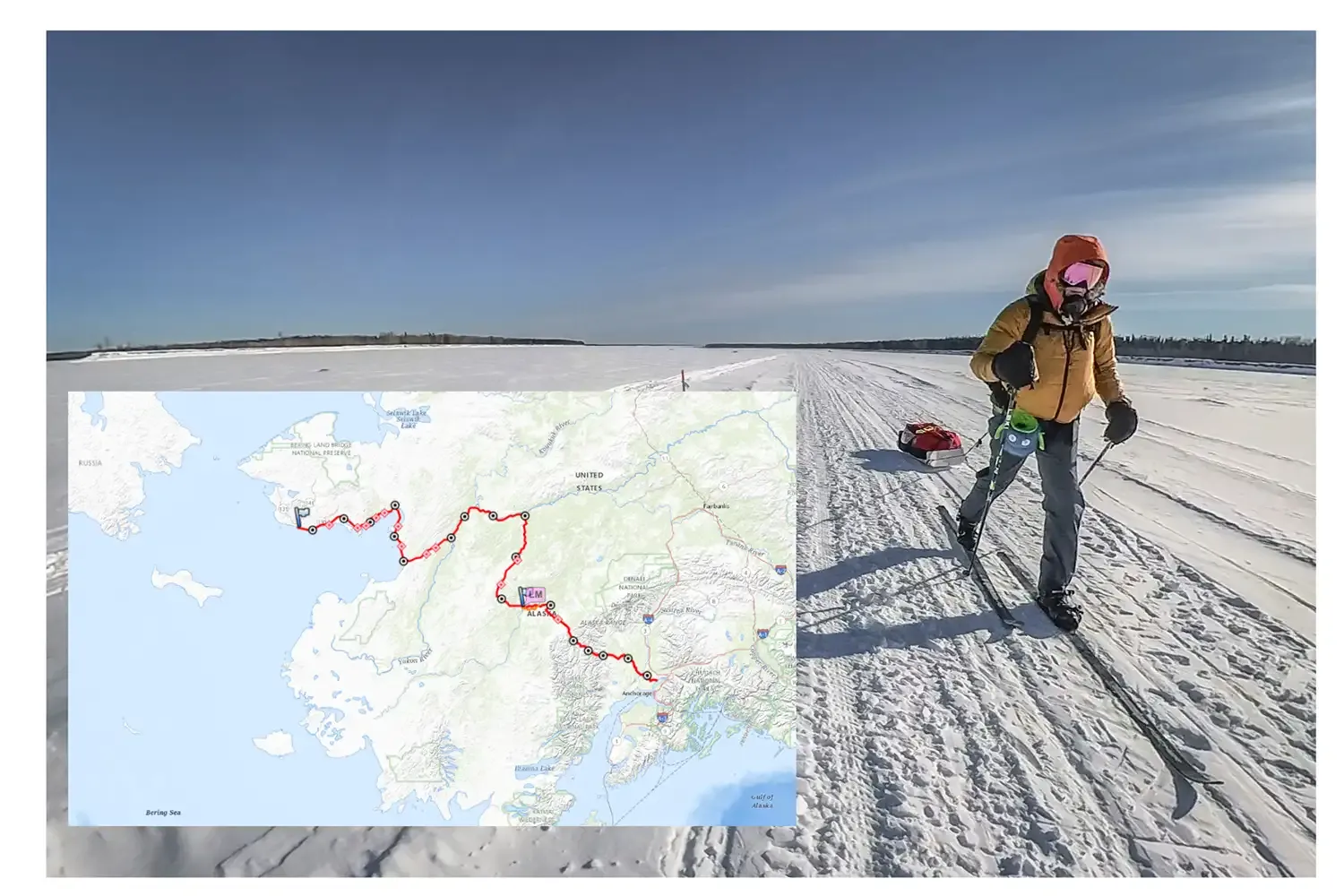

In March of 2024 I spent thirty days and nights skiing the frozen beauty of Alaska’s Iditarod Trail, almost all one thousand miles of it. Together with a hundred other racers I set out from Knik Lake near Anchorage and headed west and north. Away from the road system, across the mighty Alaska Range, through the windswept expanse of the Farewell Burn and deep into Alaska’s remote Interior, reachable only by plane or boat - or with extreme tenacity under your own or your sled dog team’s power. All of us racers where traveling on the Iditarod Trail under our own power: we were either on skis, on foot, or on fat bikes, hauling packs or sleds or both loaded with survival gear and food.

The mushers and their dogs, star athletes of the Last Great Race on Earth - the fabled Iditarod Sled Dog Race - started catching up to me some two hundred and eighty miles and nine days into my journey. They had begun their run a week after us human-powered racers; it took them less than three days to cover the same distance that, for me, meant more than a week of painstakingly slow progress.

After the dogs passed through, things got lonelier. The mushers were now ahead of me. Most of the human-powered racers were competing in the ‘short’ Iditarod Trail Invitational; their finish line was in McGrath, a village of about three hundred souls, a cafe, a clinic, and most importantly an airstrip, perched on an oxbow of the Kuskokwim River at Mile 306 of the Iditarod Trail Invitational.

Out of the roughly one hundred racers who had started the Iditarod Trail Invitational, forty scratched in these first three hundred miles. 37 finished their race in the village of McGrath. 23, myself included, reached McGrath and then pushed onwards towards Nome - another almost seven hundred miles on trail.

I had been to McGrath three times before. The next seven hundred miles were all new terrain to me: new ground to travel, new challenges to face, new growth to seek. The temperatures were punishing. Clear nights with the Northern lights dancing in the sky meant witching hours with the mercury dropping to minus forty and below - not just once or twice, but what felt like weeks on end. Having to sleep out in bitter cold and with a suboptimal glove system I injured my fingers (my toes, meanwhile, stayed toasty warm in LOWA’s Renegade Evo Ice). First, mildly, while crossing the Alaska Range in a ground blizzard. Later on, worse, while covering a 150-mile desolate stretch of uninhabited wilderness in sustained temperatures of minus twenty to minus fifty. By the time I reached the Yukon River, and a chance to get indoors at Mile 495, the frostbite on my right thumb was obvious and undeniable. A virtual consult with a friendly Fairbanks physician was my key to moving forward. “Look, yes, you’ve got frostbite.” she said on FaceTime. “But it doesn’t look too bad and there’s nothing we can do. If you were to leave the trail, we’d just tell you to wait and monitor that finger tip and see if it’ll heal. You might as well do that on the trail. Just don’t let it get cold again.”

Just don’t let it get cold again - Roger that. The forecast was calling for another five days with temperatures in the minus twenty to minus forty range. I had another 450 miles to go; to stay in the race I needed to keep making progress along the Yukon River, notorious for being even colder than the surrounding hills: cold air pools in valleys and depressions, and the barren expanse of a massive frozen river offers no protection from the wind. I pushed on.

Endless travel on the Yukon River. Overland across the haunted Kaltag Portage Trail, past Old Woman Mountain and her moody spirits, towards the windswept coast. From the welcoming safe harbors of one Inuit village to the next, across the Norton Sound along two dozen miles of slowly flooding sea ice far off the shore, I kept pushing on. For thirty days and thirty nights I kept making slow and measured progress until, eventually, after close to nine-hundred fifty miles of solitary far out travel I could see the lights of Nome sparkling in the distance.

By the time I pulled my sled through Nome’s mid-day traffic down Front Street, searching for the Burled Arch that would mark the end of my time on this adventure, it had been almost three weeks since my initial frostbite injury. The tip of my thumb was still cracked and black but no longer painful. The damage was superficial enough, the Iditarod Trail long enough, that my injuries were mostly healed before I even crossed the finish line.

I reached the Burled Arch in Nome at 2:06pm local time on March 26, becoming the first woman to ski the length of the Iditarod Trail within the context of the Iditarod Trail Invitational and, barely, within the race’s thirty day cutoff. Finishing the Iditarod Trail Invitational 1000 is an understated thing: a race volunteer, maybe onlooker or two, a handshake, a photo under the Burled Arch. There is no prize money involved with this race, no big trophies, no glory.

What was the reward, you may wonder? It was to stop moving - and also to *have* moved for that long, that far. The difficulty and the struggle of skiing a thousand miles was just as rewarding as the sweet relief of stopping, knowing that I had found ease not because I had chosen it instead of difficulty but because I had earned it by making it to the far side of difficulty. Being able to do hard things is a gift; having the choice to meet challenges on your own terms is a privilege. It feels impossible to fully frame the extraordinary gift of this adventure in words that do it justice, so instead I’ll leave you with a few moments from the trail that still capture my imagination weeks after I returned home from Alaska.

The Glare Ice Scare

After leaving the Yukon River and reaching the coast in Unalakleet my next task was to make it to Shaktoolik, a small village on the coast at trail mile 747. This was a forty+ mile day, and it got dark long before I reached town. The trail took me over some hills and then down to the sea ice which was completely blown clear of snow - glare ice; there was a strong tailwind gusting to 25 or 30 miles per hour. I surveyed the scene by headlamp before committing to the ice; my high beam penetrated the dark a few dozen yards in front of me, but all I could make out through blowing snow was one sole trail marker indicating my general direction of travel; beyond that, I could see no trail, no markers, and no obvious destination. I had no choice but commit to trust the solitary marker and commit to forward progress.

The minute my skis touched the glare ice I lost all control: the wind grabbed me and my sled and I shot across the ice as if launched from a cannon. I screamed in terror. The elements had full control over me; I had no way to stop or even just slow down. All I could do was point my skis in the direction I wanted to go in and try hold on. I stayed upright for no more than half a minute before crashing at high speed. Even after I was down I kept getting blown across the ice like a rag doll and took forever to come to a stop. It took me even longer to get my heart rate under control, and take my skis off to delicately dance across the glare ice on foot relying on the few sheet metal screws that I had studded the soles of my LOWA boots with for traction in icy conditions. At least the wind was roughly blowing in the direction I wanted to go; if it had come from a different direction, I was seriously worried about getting blown out towards the open ocean and not being able to do anything about it.

Embracing Loneliness

While I traveled solo for 98% of my time on the Iditarod trail, I frequently found myself in the general proximity of other racers encountering friendly faces on a daily basis at checkpoints once a day or so - if not more frequently. The notable exception was the stretch between McGrath and the Yukon River, after the last dog team and the motorized Iditarod Trail sweeps had passed me. I was the very last racer in the Iditarod Trail Invitational, and knew that nobody else was coming behind me. I did not see a single soul from Carlson Crossing (Mile 373) almost all the way to Ruby (Mile 495), a distance that took me close to three days to traverse on skis. The temperatures were brutally cold during this stretch of the expedition - in the -30 to -40F range and cold enough for me to get frostbite on my thumb - and I had a moment or two when I felt like I was the only person left on this planet. The Alaskan rule of “you are your only option if you get in trouble” certainly hit home at that point.

Epic Cheer and Support

The reward for making it to the Yukon was a double-edged sword: it meant reaching a more populated area with a bit of snow machine traffic and villages aka indoor access every thirty to fifty miles, but it also meant 135 miles of monotonous and frigid travel along the massive Yukon River. That said, I was lucky with my timing: my stay at Ruby (mile 495) coincided with a visit from the race director, Kyle, a pilot, who was traveling along the race course in his plane. I left Ruby in the darkness of the early morning hours to put miles down while Kyle and operations director Adrian were still blissfully asleep. A few hours later, they buzzed me in Kyle’s plane - and airdropped a care package full of meat sticks, chocolate, and Fireball for the ultimate DoorDash Lunch Delivery, Yukon edition.

Another unexpected and amazing moment of community support happened further down the trail, in between the villages of Elim (Mile 836) and Golovin. After a few days of wet snowfall and warm temperatures the trail was buried and impassable to all modes of human-powered travel - foot, bike, or ski; several racers tried to break trail and gave up because the task was physically impossible. There were a total of six back-of-the-pack racers stuck due to trail conditions. After almost four weeks and eight hundred and fifty miles of difficult travel, we were facing the possibility of not being able to finish the race a mere hundred miles from Nome due to factors outside of our control. Learning about our predicament, the mayor of Elim came out on his snow machine near nightfall to cut trail for us to the next village. By the next morning, we had wonderful smooth trail with great travel on to the village of Golovin some 26 miles away, and a few days later all of us racers ended up making it Nome.

Photo credit: Sunny Stroeer